Decades ago, Nehru told the industrialist JRD Tata, "NEVER talk to me about the word Profit. It is a DIRTY WORD."

There has been much talk in the last few years about the deepening of the Indian Power Markets. Despite all the hype, Indian Power Markets lack any resilience as was obvious during the ongoing power crisis that swept the country.

The biggest cause for this turmoil is the state attitude towards profit and free markets. This gets manifested through interventions hampering the progress of power markets. With the introduction of Power Exchanges in 2008, things were slowly changing for the last decade-and-a-half, but not enough.

Nehru was not alone in his mistrust of profit and free markets. The origin of this misguided thinking can be traced back to our historical roots, cultural reasons, societal construct, films, state-business relationships etc.

Before getting into the rabbit holes of Price Controls, here is a primer on what explains most of what we see on profits and free market thinking in India.

India's caste system gives higher respect to Brahmins (priests) and Kshatriyas (warriors) than it gives to Vaishyas (traders). Evidently, the traders are accepted but not respected in our culture.

Cinema is a mirror of society. The word profit has been vilified there too. Many old and new superhit movies like Naya Daur, Mr India, Gangs of Wasseypur, etc., depict businessman as crony, profit-seeking, exploitative and corrupt.

The colonization of India was brought about by the East India Company who came to our country as gentle traders, but gradually led to economic and then political capture of the country.

In the run-up to our independence, the famous Bombay Plan put together by a group of renowned industrialists, as a way forward for Indian Industry, justified a very state-dominated command-and-control vision for the economy, as most would agree to protect their self-interests.

The economist Jagdish Bhagwati is said to have commented that while people in China have a profit-seeking mentality, the people in India have a rent-seeking mentality[1].

After Independence, our country was built on socialist principles, as Nehru's ideas for the economy were shaped substantially by Fabian Socialism, which as one would argue was the ideology of the times.

Over the years, we have witnessed the same kind of support for socialism and markets on both sides of our political spectrum. So, the country has evolved into a trap which is equally socialist and equally reformist. Unfortunately, the socialist and reformist agendas are at the opposite ends resulting in zero work done, to coin a term of Physics.

The political interference in free market enterprises has refused to subside, even with the entry of new and successful political parties like TMC and AAP.

Kejriwal famously quoted that the profits from Reliance Energy's KG D6 gas field should be capped at 10-20% only, which is agnostic to the very nature of huge risks that underscore the business models of E&P companies.

His deputy Manish Sisodia once expressed that it is a sin to make a profit in education, which speaks to itself of the deplorable state of the Indian education system.

Economists Dani Rodrik and Arvind Subramanian have argued that India's transition to high growth was sparked by an 'attitudinal shift' of the state towards a pro-business rather than a pro-market approach. Pro-business approach boosts the profitability of existing businesses. For instance, by reducing corporate taxes, easing restrictions, land at low rates, easier access to state contracts and bank credit etc. rather than a policy reform per se. Thus, favouring incumbents and producers and thereby avoiding the creation of any losers. A pro-market approach, on the other hand, focuses on removing impediments to markets, through reforms and economic liberalization. Thus, favouring new entrants and consumers creating both winners and losers in the process.

Apparently, a pro-business approach by the government develops a subservient relationship between the business and the state. Businesses retreat into the sycophancy of the state in anticipation of commercial advantage. Over time, lobbying by businesses promotes favourable decisions. A lot of reforms don’t materialize because incumbent businesses don’t want it. Thus, only the businesses capable of managing the political and bureaucratic environment are successful and prosper. Clearly, we don’t abhor profits, we just want to ensure profits are reaped by the earmarked individuals.

In such a system, as argued by Puja Mehra in her book "The Lost Decade (2008-18): How India's Growth Story Devolved into Growth Without a Story" the bureaucrats who are neither pro-business nor pro-markets; become the enablers of political and business agendas.

With Modi government and its promise of “minimum government and maximum governance” many hoped that things would change in favour of free markets. The expectation was excessive state control over various parts of the economy would be eased. However, the government backtracked its reform and retreated to protectionist and populist policies.

Recognition of the above broad-based attitude and trends suggests that power markets are not an isolated case, but rather a victim of misguided thinking on profits and free markets.

Now let us get back to the current state of our power markets.

The latest stretch of very high electricity prices on Exchanges has caused a stir. On 1st April 2022, CERC on the behest of MoP intervened and lowered the price ceilings from 20 Rs/kWh to 12 Rs/kWh. Subsequently, in a matter of few days, the Term Ahead Market of Exchanges and short-term bilateral market of traders were also capped as some buyers and sellers were taking advantage of price arbitrage between the price controlled and non-controlled markets.

The market intervention didn't just stop at the Exchanges and the short-term bilateral market but rather got more entrenched.

Next came a series of Orders from MoP. The most shocking being invoking Section 11 of the Electricity Act 2003, which forced all imported coal-based plants to be operated at full capacity. Section 11 is for extraordinary circumstances and gives the central and state governments authority to order any generating company to operate its power plants. In the past, Section 11 was invoked by states like KT, TN, KE, WB etc. for restricting the sale of power outside the state. The states were vilified by the Center for the same. It is for the first time that Section 11 was imposed by the Central Government.

MoP also directed all the IPPs, state and central sector generators to import coal to the extent of 4% and then increased it to 10% (by weight) to cover up for the dwindling domestic coal production. Failing which domestic coal allocation will be reduced to only 70% and further to 60% for any delays in meeting the import deadlines. Some of the Orders issued by MoP were changed within days of being issued. Expect more such policy reversals and flip flops in coming days and months. This hasty execution is being demanded from fragile state discoms and state gencos; while simultaneously the government has been clamouring that there is no shortage of domestic coal in the country.

Despite MoP using everything in their toolkit viz., Section 11, mandating 10% blending, penalties for not importing coal, capping exchange and bilateral prices etc., the situation is not getting any better. Demand growth is still strong with domestic coal production and stocks out of control. Both MoP and CERC reasoned protection of the consumer interest and windfall profits by few generators for this market intervention and introducing the de facto administered pricing.

The actions have generated intense debate over profit, free markets and the role governments should play in a market economy. Clearly, the price controls will not fix the bottlenecks in the coal supply chain which are more systemic. But rather buy time for the government to deal with the problems while avoiding any bad press, public outcry and political exploitation by the opposition.

What we wanted instead was a serious discussion about institutional and structural reforms that could fix the problem forever. The high prices would have anyways subsided with time as demand adjusted with receding heatwaves and easing of coal supply bottlenecks. However, price controls and sustained demand for imported coal created by MoP may only screw that adjustment and prolong the problem.

The real dynamics of the government actions and underlying problems with the price controls will be known only in hindsight. We believe that the odds are stacked against any good outcomes coming from these decisions.

In this issue of Non-Linearity, we analyse the intended and unintended consequences that price ceilings have on the power markets. We do this by first providing some explanations and then raising some questions:

#1. The electricity prices on Power Exchange touched 20 Rs/kWh for X days in February 2022 and Y days in March 2022. Such high prices were also seen about 5-6 months back in August and September 2021. In fact, August and September are the swing months in the Exchange's spot market, i.e., these are the months when electricity prices are most susceptible to price spikes and volatility. Reasons for this behaviour are many including withdrawal of monsoon (leading to low hydro generation, high electricity demand), low coal production and stock levels, coal evacuation issues etc. However, this time around, the poor management and complacency of authorities who are responsible for monitoring the demand-supply balance, coal production, coal stocking etc. carried the problem onwards to February and March. In these months, the electricity demand starts picking up with the onset of summer. (Readers may refer to this article for a similar opinion by a veteran). The immediate question that comes to our minds is what led to the price rise on Exchanges in February and March 2022?

Can the price increase be solely blamed on high electricity demand growth and the post-COVID-19 recovery seen in demand?

Was it due to the greed of some generators and discoms which were pivotal suppliers in the spot market and who exerted market power to raise the prices? If yes, why did the Market Monitoring Cell at CERC not raise red flags?

Was it in any way related to the very high imported coal and LNG prices in the aftermath of the ongoing Ukraine war?

Was it due to the perennial rot in the Indian Power Sector – the poor financial condition of discoms, political interference in tariff setting, free power etc.?

Can it be solely blamed on CIL production capacities, inadequate evacuation facilities of Railways, and slowdown in captive coal production after the 2012 SC ruling?

Was it the fault of the generators who didn't maintain coal stocks as per the stipulated norms and fell short when they needed the coal most and supply chains were tight?

Maybe it was due to all of the above? We may differ on the weightage to be given to each of the above reasons, but all of us would agree that the blame cannot be placed solely on one entity or authority?

#2. As per the CERC Order on Price Ceiling, the prices discovered on Exchanges were in dissonance with respect to the highest bids received on the sell side. The dissonance was that the highest sell bid was at 12 Rs/kWh while prices discovered were at 20 Rs/kWh. Thus, CERC relied on the naive argument that buyers were needlessly paying more, and lower prices could be discovered merely by setting the price ceiling at 12 Rs/kWh. It is worth noting here that no instance of market failure, market abuse or market domination came to light to warrant market intervention by CERC.

Let us first briefly understand price formation in Exchanges.

The DAM and RTM operate based on a double-sided closed bid auction (DSCB), wherein, the sellers bid as per their marginal cost of supply and buyers bid as per their willingness-to-pay (opportunity cost of unserved energy). The demand curve is downward sloping and supply curves slope upwards. The natural intersection of the AD-AS curves gives the uniform market clearing price and market clearing volume for all the participants. This principle of uniform market clearing price or “Pay-as-Cleared” makes it one of the most efficient mechanisms for the discovery of prices. The reason being uniform prices maximise the economic welfare of both the buyers and the sellers and is thus an incentive for both to bid their true costs, without any speculation. The policy makers should have no opinion on the price and no tools to directly control it. By introducing a price ceiling at 12 Rs/kWh, CERC has converted a DSCB into a de facto "Pay-as-Bid"[1] mechanism.

It seems CERC fixated itself on the narrow metric i.e., looking at the nature of the buy side bids as explanations for price rise. They missed a critical point of how prices are formulated in DSCB auctions when there are supply shortages i.e., no natural intersection of the AD-AS curves.

High prices are a function of underlying demand and supply. Either of these two needs adjustment for prices to return to an equilibrium state. Interventions should therefore target the precise reasons for high prices. The reason here is supply shortages. Lack of domestic coal reduced the contracted supply of discoms from PPAs, discoms subsequently flocked to the Exchange, but limited domestic coal supply also restricted supply on Exchanges. Lower supply led to higher prices, very similar to surge pricing in Ola or Uber during peak hours or during heavy rains, nothing complicated, nothing different. There are only two solutions to such a problem i.e., increasing supply or reducing demand. Unfortunately, the solution adopted by CERC and MoP does not address either, rather we argue it only aggravate the already bad situation.

Considering this, the following questions emerge:

Are there actually any imperfections in our adopted auction design for DAM and RTM which called for intervention and price ceiling? If so, why did we fail to act previously when prices have touched 20 Rs/kWh?

How is the price ceiling of 20 Rs/kWh set in the first place? Who decided this ceiling? Isn't the change in rules of lowering the price ceiling a moral hazard – eroding the social contract for sellers and buyers on the Exchange?

The AD-AS curves for each time block of the day are available in the public domain. All the market participants could also see that the highest bid by the seller was at 12 Rs/kWh and the buy side bid was at 20 Rs/kWh. Then why was it visible to only MoP and CERC? Why did the buyers jack up their bids to 20? They could have lowered their bids. Why were they still bidding at higher rates?

It seems the CERC Order implies that the prices should be discovered based on only one leg of bids which is akin to the 'Pay-as-Bid' mechanism. The buyer's willingness to pay more for allocative efficiency is not given any consideration. In that case, why should we have a DSCB in the first place?

What would happen if the buy side is not given any say in the bidding? Will certain buyers who were willing to pay more, which could be both discoms and industrial consumers get a fair deal?

What are the advantages of considering both the buy and sell sides in any transaction? What happens when market clearing is based on only the sell side bids?

The variable cost of gas-based generation as per the prevailing LNG prices was in the range of 22 Rs/kWh to 27 Rs/kWh. Bringing gas-based generation would have eased the situation but called for increasing the price ceilings. Since it was a supply-side problem, why did CERC not consider increasing the price ceiling?

CERC sought to protect consumers by restricting the prices on Exchanges but this introduces scarcity as some high-cost coal and gas generation cannot participate in any of the products. Even though sooner or later, policymakers may recognise this issue, there is a fear that the poor and vulnerable sections will be exposed to high prices. But such sections are already protected in our tariff regulations. Then what is the fear all about? Also, what fraction of electricity is traded on the DAM? Last time we checked it was less than 5% of total generation in the country. Did it warrant such massive measures and what benefits did it accrue, if any? Or was it another jumla, a sheer display of concern and associated activity?

By capping prices, the MoP/CERC has deprived the willing generators and customers to sell and purchase electricity at higher rates. This after, CIL has throttled the coal supply to CPP and industry with almost zero supplies. All this is happening when states have themselves put numerous tariff and non-tariff barriers for Open Access purchases and sales? Isn’t availability of power a sine-qua-non for Atmanirbhar Bharat?

Finally, the price ceiling of 12 Rs/kWh is based on the marginal price of imported coal plants. The committee set up under CERC showed that the marginal price of some imported coal plants could be more than 12 Rs/kWh and is dynamic depending upon the price of coal in international markets. Will CERC intervene with every increase or decrease in the price of imported coal?

#3. It is understood that the market intervention has risen from some MoP directives to CERC under Section 107 of the Electricity Act, 2003. Unfortunately, this directive is not available in the public domain, either on CERC or MoP websites. Sharing of data should be consistent with the Government's larger mission of improving access to information for all stakeholders to ensure transparency and effective public consultation and participation. As a result, there are some open questions:

Why is the MoP Order not in the public domain? Public consultation is key for free markets. How can a price ceiling be introduced on the back of some private analysis?

Why did MoP pressurize CERC to introduce a price cap of 12 Rs/kWh rather than allowing it to increase the ceiling so that gas-based generation could also participate in Exchanges?

MoP could have asked Exchanges to increase the price cap so that more supply was brought on the Exchanges. Did it not do so to cover up for the inefficiencies in its departments viz., coal, gas, and railway sector?

#4. Market intervention cannot ignore the larger structural and systemic issues. For instance, the monopoly in coal supply, the monopoly in coal transportation, monopsony in retail distribution through discoms, NPA problems etc. Should policy makers and regulators not take into consideration the interaction between intervention and its larger implications?

The supply side in India is heavily dependent on Coal. Coal India Limited (CIL) is a huge public sector monolith, which has resulted in entry barriers for the private sector in this field. The complex web of government policies, regulations and controls has made private entry into coal mining difficult and hard to achieve. Against this premise:

Isn't it obligatory for the central government owned CIL to supply coal to generators as per their contractual commitments? Honouring the Fuel Supply Agreements (FSA) is paramount when the barriers to entry in this field are massive? Should we not consider a penalty for CIL if it fails to meet its obligations?

COVID-19 disrupted the supply chains across the world, causing shortages in imported coal and LNG. The complacency of the governments world over led to the assumptions that these were temporary blips which would self-correct with time. The MoP suffered the same illusions. Who is responsible for this mess?

In such a scenario, do the price controls give the impression that the government can show they are doing something about the price rise?

Should the central government apologise for totally underestimating the problem for over a year, not assessing the coal situation and undertaking remedial actions ahead of time? Why is it only in crisis that our governments awaken?

#5. It is often seen that the incentives of ruling political parties often mismatch with that of economic rationality. Therefore, all of them use discoms as a redistributive tool to fulfil their self-interests: free electricity for agriculture, free electricity to vulnerable sections, lack of enforcement against electricity theft and purchasing electricity at high costs. These actions have placed discoms in chronically bad financial health which necessitates periodic bailouts specifically with support from the central government. The central government bailouts are typically accompanied by so-called reform packages to put an end to the problem. Albeit all such 'one-size-fits-all' national solutions have fared poorly many times across many states.

Discoms seldom recover full power purchase costs from its consumers. There is a limitation in the recovery of higher power purchase costs for discoms. Typically, it is recovered by increasing tariffs for paying consumers and payment of subsidies by the state. While a steep increase in tariffs may result in tariff shocks and consumer resentment, there is also a fiscal limit for states to increase subsidies. Therefore, the discoms unable to balance the two make financial demands from the central government. This furthers the central government's fiat transmitting its agenda of command-and-control reforms on the states.

Looking forward, the ongoing crisis might only deepen this command-and-control reform style as the central policy actions have locked all the discoms into higher costs by mandating coal imports for a sustained period, that too when the costs of coal are at an all-time high. In the absence of any financial support, these high costs might sit uneasily on the balance sheets of discoms for a very long time drying up their working capital completely. It is hard to believe that there will any break in this vicious cycle and no need for another bailout very soon.

The solution however is structural reforms that address the long-standing fundamental problem of political interference in tariff settings. The reforms should place the states on the foundation of free markets. Once states work through free markets, they will harvest the benefits of cost-minimisation without any need for central government benevolence.

The nth package which unapologetically calls itself “Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme” has already been launched. Wasn’t UDAY supposed to be the panacea for all distribution related ailments?

Typically, SERCs while approving the ARRs of discoms decide on prudent capping for short-term power purchases. These are either financial or in terms of the total quantity to be bought. Since there is already a mechanism for price control, should CERC have left the decisions to SERCs and not intervened in the markets?

What will be the impact of MoP policy mandating the purchase of imported coal on the states vis-à-vis free market purchases? We feel a pushback is inevitable?

The nature and extent of policy actions attempted thus far are not solving the fundamental problems of the Power Markets. Why do we believe that things could work differently now when the single national solutions of the central government have not delivered the desired results in the past?

Discoms are ultimately controlled by the political powers and respond to their objectives and interests. Does the solution lie in free markets without any political interference? How can this be achieved?

#6. It is often difficult and impossible to predict market participants' actions as well as market outcomes beforehand. In the absence of any counterfactuals – what might have happened to Exchange prices in the absence of a price ceiling? It is hard to point out the evidence for whether price controls are really such a bad idea. Therefore, we must think about how we believe the markets work by relying on basic economic theory.

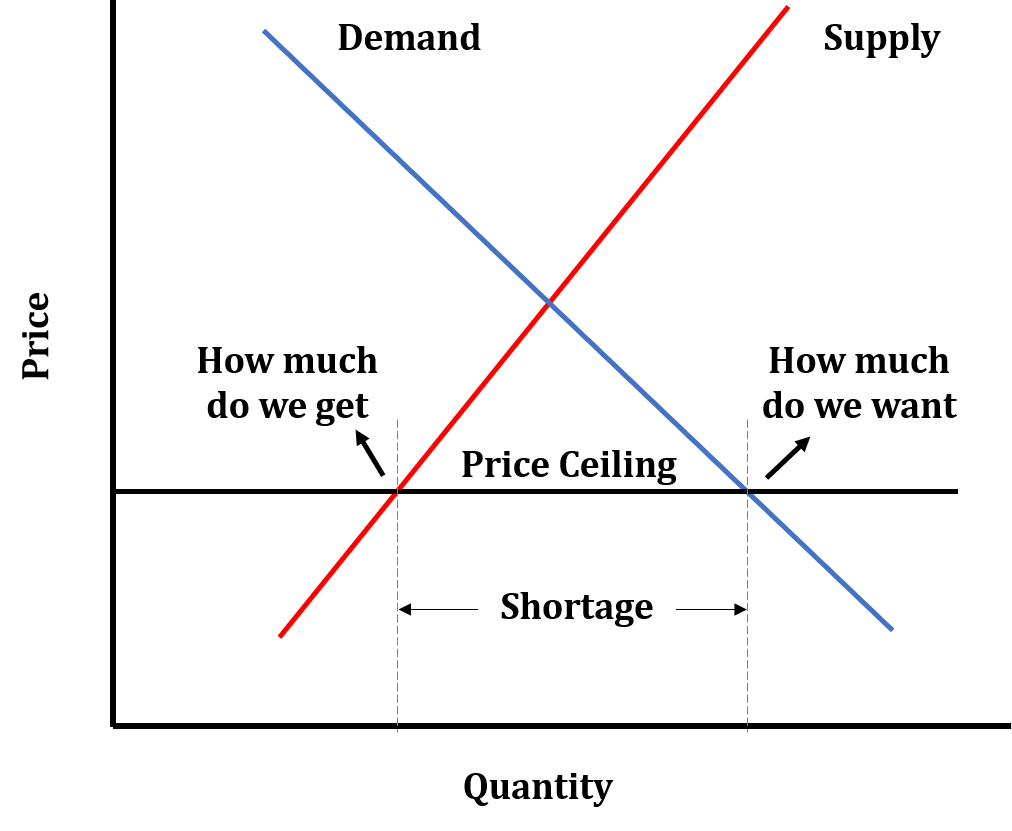

Econ 101 of the aggregate demand and supply (AD-AS) curve shows that the price ceilings will cause shortages. Below is the graph showing the theoretical shortage when the government puts a price ceiling.

Because the price ceiling pushes the price down from the natural intersection of the AD-AS curve, buyers want to buy even more, while sellers are willing to sell less than they would be willing to sell at a higher price. The result is 'shortage'.

The shortages then give birth to misallocation or allocative inefficiencies further complicating the problem. After all, with a price ceiling, there are simply not enough units to satisfy demand. Therefore, mechanisms need to be devised for which demand bids get satisfied and which demand bids remain unsatisfied. The price ceiling, therefore, has negative consequences not only for the sellers but also for the buyers i.e., the party whom the government meant to protect by imposing the price ceiling.

But one would argue that simple theories based on the AD-AS curve may not always be sufficient for determining policy action. The real Power Markets are much more complex. There are expectations and beliefs, concentration of buyers and sellers, lop-sided playing fields, coordination and information problems, entry barriers and all sorts of complex stuff. So, it is possible that counterfactual would have led to some unusual effect.

One thing though is clear, a price ceiling would boost demand because it enhances the purchasing power of discoms, which will lead to even more shortages, causing the government to respond with even more price controls. That would lead to the possibility of an unpleasant spiral causing fear of shortages to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

So, when price controls become the government's primary tool for fighting price rises, it could send a very dangerous signal. It could convince the investors that the government doesn't trust the markets. Without price controls, while the immediate response of the market may be inefficient in the short term, but in the long run, the invisible hand of markets makes all adjustments and clears out all the inefficiencies. Therefore, rather than using regulatory fiat, the creation of incentives for market participation in the long run would be a good step forward. And, to paraphrase Keynes, in such long-runs, 'WE ARE ALL DEAD'. But if we don't think of the long term while we are navigating the short-term, 'WE ARE ALL DEAD TODAY'.

Based on the above, one might also argue that the price caps act as more of a demand-side rationing mechanism since it does nothing to improve supply. When bidders observe that the supply offer is limited, despite knowing that the maximum ask is 12 Rs/kWh, they bid a higher price in a race to outbid each other. Finally the bids of willing buyers reach Rs 20/ kWh, which is the maximum bid allowed on the Exchanges. This inherently allows buyers who value electricity the most to procure it. When price caps are introduced, there is no mechanism to value electricity rather every buyer bids 12 Rs/kWh (again the cap) and the limited supply volume is distributed to the buyers in the proportion to their demand. So the demand-supply stacks and underlying competition lose all their significance and we enter a classic regime of the state dictating the consumption quantity. Are these baby steps towards a more centralized command and control mechanism?

Another question that arises here is, did anyone not see the crisis coming? While we are certain that MoP did not, we believe that the collective wisdom of the market might have anticipated it. Had there been a robust and liquid futures trading segment akin to those for other commodities, futures prices would have signalled the crisis and participants might have taken early corrective actions to prevent this crisis. While there are active discussions around the launch of electricity derivatives, the price-cap incident will shake the foundations of such a market before its launch. Settlement in futures happens with reference to the spot prices, and arbitrary imposition of price caps will disturb the settlement process and give rise to more confusion, disputes and litigation thereby increasing transaction costs significantly

#7. One might argue that price controls are not always bad. They are sometimes useful. For example, if the country under question is undergoing a war, during natural calamities or in case of market failures. Kelkar and Shah in their book viz., In service of Republic – The Art and Science of Economic Policy emphasize that policy makers need to learn to respect the prices that come out of the large numbers of voluntary buyers and sellers. Sometimes, the prices go wrong because of market failures. If so, the solution lies in addressing the root cause - the market failure which they characterise as the following:

Market Power,

Negative Externalities,

Asymmetric Information, and

Public Goods.

Certainly, price controls as a tool for fighting consumer interests don't feature anywhere and are a very bad idea. Price controls have unintended consequences on the consumers because it reshapes the incentives of the investors. In the absence of a stable and coherent policy, the investors will be subjected to mixed signals and heightened policy risk. The investors are wary of the policy instability as it would jettison their investments in future. Therefore, they respond less and adopt a 'wait-watch-see' strategy for markets. Thus, the real dangers of using price controls as a consumer protection policy as adopted by CERC and MoP are its unseen effects. These are summarily the following:

What is the signal that the price ceiling sends to investors and therefore new capacity additions specifically the investments in energy storage?

What is the possibility that electricity shortages will be exacerbated by price ceilings?

What is the possibility that surplus in excess of needs i.e., spare generation capacities will not be created?

What is the possibility that higher prices which are in the order of the artificial price ceiling get entrenched in the market?

#8. Now we turn to a classical section on international experience. No essay on power markets in India would be complete without giving it enough space. Our policy makers are more often than not seduced by ‘isomorphic mimicry’[2] – what happens in advanced and mature power markets during such crisis? what is the magnitude of price caps in these countries? This fascination about transplanting ideas from advanced power markets into our country is misplaced. In advanced power markets, there are many checks and balances emanating from the legal and institutional environment that supports the underlying foundations and superstructure of the market design. Those are often lacking in India. A mere lift and shift of their ideas to our system often results in difficulties because the remaining checks and balances are lacking.

In the United States (US), almost all RTOs/ISOs, except ERCOT, have resource adequacy construct, wherein capacity availability is ensured through regular planning. In some cases, like CAISO and SPP, load serving entities (discoms in Indian parlance) are mandated to demonstrate adequate capacity commensurate with their demand obligations through bilateral contracts. In other RTOs/ ISOs like PJM, NYISO capacity market auctions are run wherein the RTO/ISO is responsible for running a centralized, mandatory auction to procure capacities on behalf of load-serving entities. MISO has adopted a hybrid alternative with bilateral procurement coupled with a voluntary capacity market auction. These mechanisms allow suppliers to earn revenues in addition to revenues from the sale of energy for a commitment to be available to supply at every point in time thereby mitigating the risks of supply shortage.

In ERCOT, the task of ensuring resource adequacy is also market based. The spot prices are allowed to rise to very high levels during periods of scarcity, which sends out signals that demand is inching towards supply and the market would need more suppliers. Since the new suppliers would be operating only during periods of scarcity, hence the realizations during these short periods should be high enough to recover their investment and operating costs. Accordingly, the price cap for the cost of generation (the highest price a generator can charge for electricity) has increased over the years from $3,000/MWh in 2011 to $9,000/MWh today[3].

In Germany, resource adequacy is maintained through a mechanism known as Strategic Reserves, wherein the system operator sources capacity and the same is kept out of markets, i.e., not allowed to participate in energy or balancing markets. Only in cases of crisis wherein the energy markets fail to clear, the system operator calls upon the selected providers to supply energy

In Nordpool, any price indeterminacy due to a non-natural intersection of demand and supply curves is first handled through rebidding. Rebidding can bring new supply on the exchange which is costly and was not bid earlier. It may also lead to demand response as some of the price-sensitive demand may opt out in anticipation of higher prices.

An important distinction however is to be made. In all likelihood, the recent power crisis in India may not be attributed to a capacity shortage, it appeared to be more of a fuel shortage. As such even resource adequacy constructs may have failed to mitigate the risks unless fuel markets are deregulated or prices on spot markets can rise to higher levels, like ERCOT, to allow RLNG and imported coal to be used as feedstock in the plants.

#9. It is an old cliché that "Never let a crisis go to waste". Some of the most critical reforms in the Indian economy have taken place when our backs were against the wall. The balance of Payment crisis led to the 1991 reforms which liberalised our economy, 2G Gate and Coal Gate resulted in a fair and transparent allocation of resources, NPA crisis led to Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). The present crisis in the power sector is also a perfect storm. We are not going to have an opportunity like this again for a very long time. Given that a crisis is also an opportunity, the high price trends witnessed on Exchanges may not be as bad as they are being made out to be. Probably, we need to take a lot of pain in the short-term, if we want a less volatile and resilient future. The trade-off is the political risks due to high short-term prices and the benefits of a free-power market economy. In public policy parlance, this calls for a political manoeuvre which would create a smokescreen against all odds to push the much-needed structural reforms. Something akin to Chinese revolutionary leader and statesman Deng Xiaoping, who had this remarkable ability to radically change a system, all the while pretending continuity and talking about continuity. The reforms carried out by Deng gradually led China away from a planned economy, opened it up to foreign investment and technology, and introduced its vast labour force to the global market, thus turning China into one of the world's fastest-growing economies. Here are the questions that arise now:

What holds us back from undertaking deep structural reforms in the electricity sector, even crisis after crisis?

Should the government care about short periods of very high prices or correct the long arc of history by undertaking the much-needed structural reforms in electricity, coal and gas markets?

Who would be India's Deng navigating us out of the present crisis?

We will end now. Here is the conclusion:

Conclusion:

It's no wonder, that the late American President Ronald Reagan once infamously quipped: "The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the government and I'm here to help". Reagan was referring to the belief that the government, in general, is incredibly inefficient in everything that it does, sometimes to an extent that its attempts to help instead end up harming those it wanted to protect in the first place. Reagan believed in federalism and free markets. Reaganomics led to one of the longest and strongest periods of economic growth in the United States.

The power markets in our country, so far, have been shaped by state domination with a distinct pro-business rather than a pro-market approach. The toolkits being put in action include interventions through policy and regulatory fiat, centralisation through command-and-control measures albeit with a carrot and stick approach. But a lot of what the state has been doing hasn't worked out as our power markets are still flailing. That's what the development economist Lant Pritchett calls the "state capabilities trap". The problems have become so entrenched that it is now hard to fathom that simple market-based mechanisms may provide the ideal solutions.

Our private sector, which predominantly consists of large domestic players, has also remained far less interested in removing any impediments to competition and deepening the power markets. Rather, they have lobbied to garner political support for non-market mechanisms-based growth. Obviously, pro-business orientation is in their own self-interest. The private sector which is otherwise so crucial for providing the policy and regulatory feedback has therefore retreated into subservience of the omniscient and benevolent central and state governments.

What can be done? Is there any hope?

The government must value profit over populism and adopt a pro-market orientation. Steven Vogel in “Marketcraft: How Governments Make Markets Work” illustrated how the free markets need to be crafted by individuals, firms, and most of all, by the governments. State regulation and market competition are not zero-sum, if they work well, they may enhance each other. Rather than “deregulation”, Vogel views market reform as “reregulation” entailing more rules, adopting new business practices, and diffusing market norms. The United States, one of the "freest" market economies, is the most heavily regulated country. Thus "marketcraft" represents a core function of government comparable to “statecraft”. (More on this in our next newsletter)

Only then will the private sector engage in the process of risk-taking. The fruits of such a transformation would be lower costs to the economy and consumers. Without power markets, resource allocation gets distorted, and the costs induced upon the economy are massive.

Free power markets operated on the principles of demand and supply discover the most efficient prices. The price system sends signals shaping the decisions of all sellers and buyers. In such a system, investors constantly respond to incentives, prudently expanding and choosing generation capacities and generation mix while customers modify their consumption patterns. Profit is not a DIRTY word as it is no longer assured in power markets. It fluctuates and investors are exposed to risks. This creates winners and losers. Some companies fail and go into bankruptcy. New managements acquire them and try to turn them around. All of this is normal in a power market economy. On the other hand, any and every government-imposed control on markets and prices reduces the effectiveness of such coordination.

The US Shale Oil and Gas Industry is an ideal example of a market economy. Shale is the backbone of the US economy. The US became a net exporter of oil with the Shale revolution. Profit is not something that comes about easily in this industry. It is the reward for creativity, innovation and risk-taking. The risk and reward are omnipresent in the Shale industry and constantly shape operational decisions and investments. The industry works on the principles of how to change course in a way that maximises profits.

The coming decades will see massive technological and business model change with renewables, batteries, electric vehicles, etc. Therefore, the deepening of power markets is the only way forward. Undue influence from the government may result in shallow markets and send wrong signals, eroding the credibility of markets.

No government intervention is as certain to do damage to the spontaneous order of the market economy as price controls can do. History is a testament to the fact that no amount of central command and control has achieved what distributive intelligence of market participants taking voluntary actions in their self-interest has achieved. It is imperative that governments must step back and allow markets to shape the next order. Central command and control measures create distortions and have frictions and costs. Our country needs the electricity sector to flourish for lifting its people out of poverty. Market-based growth would be the right way forward out of this crisis.

[1] For more details on Pay-as-Bid vs Pay-as-Clear, readers may refer to this excellent presentation https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/sites/default/files/docs/2012/10/pay-as-bid-or-pay-as-clear-presentation.pdf

[2] ‘Isomorphic mimicry or ‘Isomorphism’ are terms in biology which refer to different organisms evolving to look similar without actually being related. Isomorphic mimicry is the process by which one organism mimics another to gain an evolutionary advantage. In public policy parlance, isomorphic mimicry is the tendency of governments to mimic other governments’ successes, replicating processes, systems, and even products of the “best practice” examples

[3] Recently there has been a decrease in the price cap from $9,000/MWh to $5,000/MWh

[1] Profit-seeking is the creation of wealth, while rent-seeking is "profiteering" by using social institutions, such as the power of the state, to redistribute wealth among different groups without creating new wealth. [https://en.wikipedia.org › wiki › Rent-seeking]

just discovered your content.. looking forward to reading more. keep up the good work.

True, I agree to a large extent. Additionally in the Indian context, it needs a tacit political consensus. The governments and the oppositions need to tango on the matter covertly, as they did in Delhi discom case.