CHAPTER ONE: THE BEGINNING

Here is how it all started.

A budget speech, of all things, on July 24, 1991, during a time of political unrest and economic hardship, set India on the path of economic liberalization.

India's finance minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, declared that the nation would embrace markets after decades of socialist planning. The reforms paved the way for introducing competition in different sectors. So began the tale of power markets in our country.

Within three months, the Ministry of Power1 (MoP) unveiled a new IPP policy to allow private investments in the generation sector. By the mid-1990s, memorandums of understanding (MOUs) for 75,000 MW capacity were signed. However, only a handful of these projects were completed by the late 1990s.

The IPP policy was heavily setback due to the opaque way of project allocation and the disproportionate risk-sharing mechanism in its PPAs.

This led to a series of legislative and policy steps by the central and state governments during the 1990s which culminated into the first draft of the Electricity Bill on February 26, 2000.

In the preface of the report to the draft Electricity Bill 2001, Dr. Gajendra Haldea2 said of the power markets:

“The rationale for open markets is exactly the same as the rationale for democracy. They have the same flaws and strengths, and they go together”

While the Executive Summary of the Bill noted the following:

“The absence of competition in generation and supply of electricity must be viewed as a form of government interference that would restrict the evolution and operation of a free market. Introduction of competition in electricity markets has resulted in significant gains for consumers in several countries and must be viewed as a cornerstone of the reform strategy in India”

The passage of the Electricity Act, 2003 in June 2003 marked a turning point for the power sector. It made clear the intention of transitioning to a market-driven mechanism.

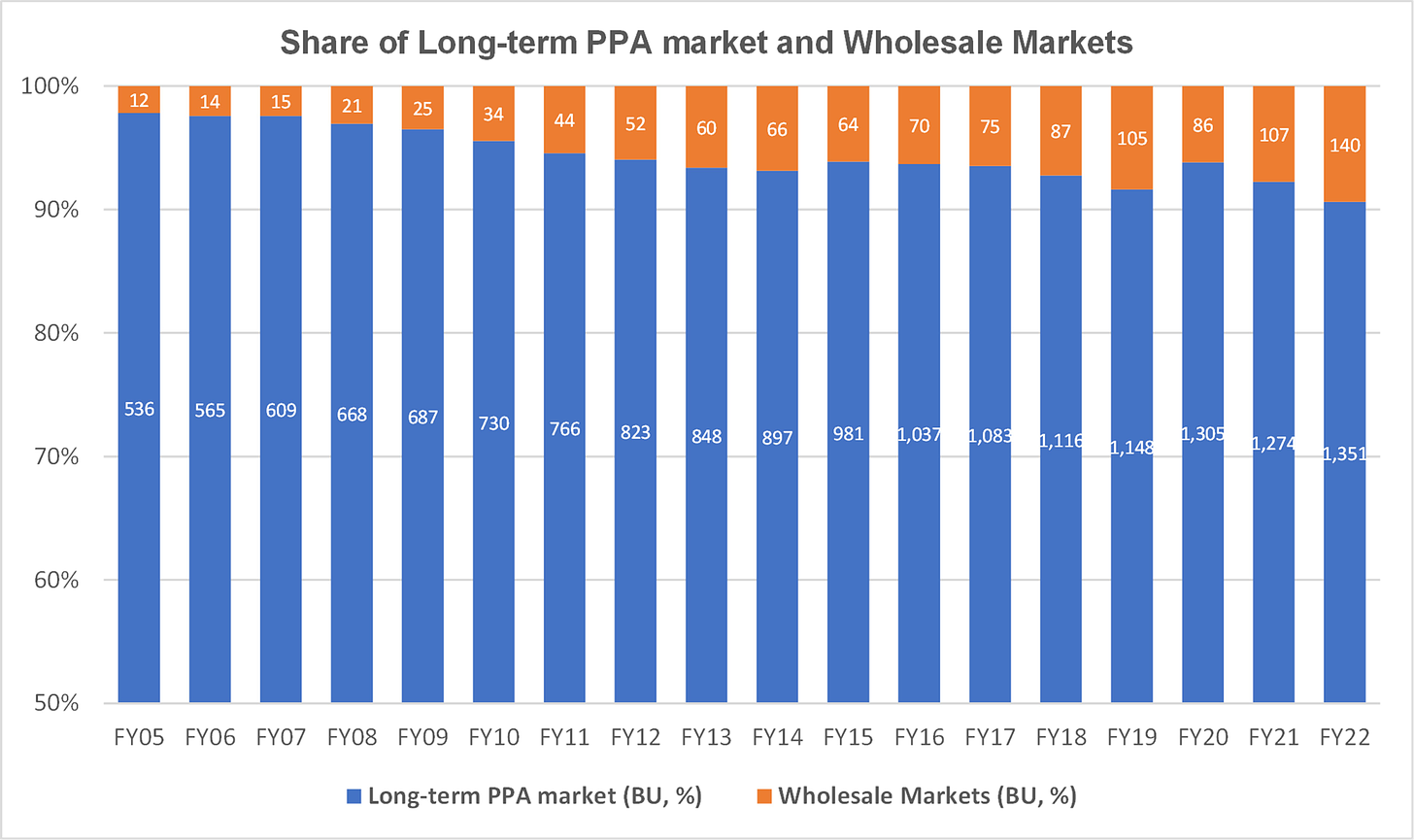

The market design that has evolved since the Electricity Act, 2003 comprises of a “two-tier market solution”. The first tier of this solution is the physical delivery based long-term bilateral PPAs. Typically, dominated by baseload round-the-clock (RTC) contracts from coal-fired power plants with a tenure of 25 years. The long-term PPA market has its own ecosystem for auctions, transmission connectivity, access and pricing, scheduling and dispatch. The second tier consists of a voluntary pool with a price-based system for spot markets (day-ahead and real-time), short-term bilateral market, and imbalance mechanism3. This market is operated through Power Exchanges, MoP’s DEEP4 portal and over the counter (OTC) bilateral contracts through power traders. From now on, we will refer to the second tier as the “wholesale markets”. The wholesale market like the long-term PPA market also has its own ecosystem for auctions, transmission connectivity, access, and pricing, scheduling and dispatch. Therefore, the two markets have existed in parallel with distinct grid planning and operating principles.

As is evident from the above graph5, in the “two-tier market solution”, the wholesale market has been reduced to a lower share and has stagnated. The long-term PPA market is favored and has higher shares. The policy and regulatory apparatus supports it, the businesses prefer it and discoms are hostage to it. Therefore, this market has expanded fast. While the wholesale market had to struggle a lot. Within the wholesale markets, the day-ahead market has saturated at 50-60 BU per year while the short-term bilateral market has fallen to 25-30 BU per year from a peak of 40BU. The growth of 30-50 BU seen in FY21 and FY22 is due to introduction of new markets viz., RTM (20-30 BU), GTAM (10-15 BU) and GDAM (5-10 BU).

What explains this skewed share across the long-term PPA market and the wholesale market over such prolonged periods?

Our fundamental hypothesis is simple, the policy and regulatory apparatus for “two-tier market solution” unduly favours the long-term PPA markets over the wholesale markets. In other words, the playing field for the two markets is tilted towards the long term PPAs.

There is an inextricable relationship between growth in any market segment and the policy and regulatory apparatus governing it. The relationship has been best described by Steven Vogel in his book “Marketcraft: How Governments Make Markets work6”. Vogel has demonstrated through examples how markets don’t evolve naturally. Rather, they need to be crafted by governments. Accordingly, the wholesale markets in power will also not arise naturally. To do well, an enabling policy and regulatory environment will be required.

CHAPTER TWO: THE PITFALLS

In this chapter, we will scrutinize the evolution of the “two-tier market solution” and critically analyze the aberrations in the policy and regulatory apparatus that led to this skewness in market shares.

The Electricity Act 2003 was the country’s biggest commitment to markets and private sector participation. The Act among other things delicensed generation. A comprehensive institutional framework including policy, technical, regulatory, financial, and legal system was introduced. This enabled enforceable, durable and complete contracts in the form of long-term PPA market.

However, from the very beginning, the intellectual commitment to market design was prejudiced towards long-term PPA market over the wholesale markets. This was despite a functional short-term market as early as 2003 and introduction of Power Exchanges by 2007.

MoP framed the competitive bidding guidelines in 2005 for promoting coal-fired baseload long-term PPAs. Case-1 and Case-2 were its two provisions. This was important to move away from the earlier system of discretionary selection of projects under the ‘1991 IPP policy’ and incentivized private sector participation.

Case-1 and Case-2 auctions generated massive interest from the private sector. It not only attracted the big private sector companies in power and infrastructure, but also non-infrastructure and cash rich companies displayed great interest in competing for long-term PPA market. Thus, a very large pipeline of shovel ready coal-fired capacity was created anticipating future bids. By 2007-2008, about 30-40 GW of PPAs were signed with private generators including two UMPPs.

This necessitated an overhaul of the policy and regulatory apparatus governing the following:

Grid planning and operations including transmission connectivity, transmission access, transmission pricing, scheduling and dispatch

Policy for coal allocation and pricing

Improving the efficiency of public sector generators

Development of Power Exchanges

Introducing the Missing Markets

Expanding the Power Trading

Supporting Financial systems and banking regulations

We argue with reason that the above reforms manifested in accordance with the needs of long-term PPA markets. This has impacted the wholesale markets negatively. We will go into the micro analysis and examine how these changes have been partisan to the wholesale markets and what have been the pitfalls. So, let us take a step back to first principles and start looking at them one at a time.

Pitfall #1: Grid Planning and Operations – Long term PPA market takes the cake

CERC formulated the open access regulations for connectivity and long-term access (LTA) in 2009. The regulations were grounded in the deep grid connection philosophy7. The cardinal principle used here was to underpin the entire investments made in transmission through LTA customers. The short-term open access (STOA) regulations for bilateral contracts and Power Exchanges were notified in 2008. The regulations were grounded in shallow connection philosophy8. The cardinal principle used here was that no new transmission investments will be undertaken for STOA customers. The STOA will be allocated after meeting the requirement of LTA customers on the residual capacity in the transmission system.

Furthermore, LTA could be granted without a corresponding PPA. But for operating an LTA, a corresponding long-term PPA was a must. A generator could not utilize its LTA for transacting in the wholesale markets. Since STOA was dependent on the residual margins available after LTA, new generators seeking connectivity were also compelled to avail LTA in order to have the transmission system in place. Thus, LTA was implicitly made a pre-condition for connectivity.

The CERC philosophy of having separate open access rules for long-term PPAs and wholesale markets led to distortions in transmission access, transmission pricing, scheduling, and dispatch methods.

Long-term PPAs dispatched through LTA had guaranteed access to transmission. While for the wholesale market, transmission access was at risk even after acquiring LTA. As a result, LTA was of no use for the wholesale market. Merchant sellers received low priority on the transmission system. This raised the risks for transacting in wholesale market.

Transmission access and scheduling were separate services in LTA. A long-term PPA holder could nominate schedules a day in advance, and then revise the schedule four-time blocks before dispatch, which was later changed to seven-/eight-time blocks. However, for the short-term bilateral contracts, the transmission access and scheduling were tightly coupled as a single integrated service. Therefore, the short-term bilateral contracts couldn’t be rescheduled like long-term contracts. The inability to revise a short-term contract closer to dispatch increased the costs of transacting in wholesale markets compared to long-term PPA markets

Both LTA and STOA were point-to-point allocations and contract path dependent, which resulted in another problem i.e., pancaking of transmission charges. The issue of pancaking was resolved with Point of Connection Transmission Charges (Sharing Regulations) implemented in 2010. However, the LTA customers had to pay a fixed charge in the form of Rs/MW/Month. The short-term and collective transactions paid in the form of Rs/MWh. Wholesale market participants who had also obtained LTA had to pay both the LTA and STOA charges. This also increased the transaction costs for wholesale market users.

It was only through General Network Access (GNA) Regulations in 2022, that we were finally able to bring some sanity in connectivity, different forms of transmission access, decoupling access & dispatch and harmonization of transmission pricing for our "two-tier market solution". It took eleven (11) government committee reports9 spanning over ten (10) years to transcend our open access philosophy for transmission to GNA.

As Isher Ahluwalia says:

“Nothing gets done by writing it in a government committee report, but nothing ever got done without it being repeatedly written into multiple government committee reports”.

Pitfall #2: Coal Allocation Policy – Selective Benevolence

Liberalization took place in the electricity sector only. The coal sector was not liberalized. Coal India Limited (CIL) continued to hold the monopoly on the fuel. Therefore, the coal supply continued to be discretionary with administrative pricing mechanisms, and distortions. Only generators who had secured long-term PPAs with discoms had priority for coal allocation. Monopoly supplier couldn’t ramp up output to meet the demand of wholesale markets.

Coal was rationed to long-term PPA holders. CIL FSAs guaranteed only 60% of the actual contracted quantity (ACQ), wherein even the ACQ was also not as per the normative 85% PLF requirements but restricted to 60-70% threshold only. This led to even more demand for long-term PPAs from discoms as existing PPAs would inevitably fall short on energy delivery. Long Term PPAs therefore became the gate-pass for coal supply from the monopoly supplier.

In the absence of a coal distribution policy for merchant plants, the costs and risks of sourcing coal increased for wholesale markets. However, the long-term PPA holders were still entitled to full fixed cost recoveries from discoms as they could show 85% availability using imported coal. This also led to increase in operating costs of merchant generators.

With improvements in coal supply, particularly after 2015-16, the merchant plants had to still run at significantly higher coal costs and compete on the spot markets with low-cost surplus power from discoms (thanks to coal supplies at preferential rates). When spot markets are inherently notorious for the "missing money problem10" which limits recovery of fixed charges to infra-marginal rents. Distortions in variable charges of merchant plants just compounded the difficulties for wholesale markets manifold.

Pitfall #3: Section 62 PPAs – Coercive Paternalism

With the success of UMPPs and other big projects, the private sector's entry into the state-dominated power industry was heralded with great excitement. Section 62 and Section 63 are the two provisions for long-term PPA market in the Electricity Act 2003. Section 62 is the cost-plus tariff route. Section 63 is the competitive bidding-based tariff discovery route. The policy while adopting the Section 63 for private sector kept the back door entry open for public sector enterprises through loosened timelines for Section 62 projects. Instead of replacing or forcing the public sector to compete, the policy focused on increasing the entry of private long-term PPAs alongside the public sector long-term PPAs.

The largest generator in the public sector today, i.e., NTPC, benefited most from this policy loophole. Prior to the sunset clause i.e., the year 2011 for competing with the private sector in auctions, it signed 40GW of long-term PPAs with discoms hurting the private sector. Private players complained and went to CERC. These events left even less room for any capacity addition through wholesale markets.

Pitfall #4: Power Exchanges – Adding an Aura to wholesale markets

Development of the Power Exchanges was the last step in the sequel to market philosophy as envisioned in the Electricity Act 2003. By early 2005, policymakers had come to consensus that some form of transparency in price discovery for short-term bilateral market was desirable. None, however, appeared eager to advocate a full-fledged wholesale market (with voluntary or mandatory participation) as was seen at that time in other parts of the world.

According to the CERC's discussion paper “Developing a common platform for Electricity Trading11 which was floated in June 2006:

Short-term trading through Open Access constitutes 2-3% of the total supply. The market lacks depth. It is dominated by limited number of Suppliers having limited quantum of tradable power (Para 1.2.3)

It is generally not advisable to disturb existing long-term contracts for the sake of market development (Para 4.1.4)

At present, electricity can be traded bilaterally at mutually agreed rates. There is a need to further develop short-term trading to bring equity, transparency, and efficiency in trading (Para 1.2.6 & 4.1.1)

Short-term trading is essential for resource optimization and meeting peak demand (Para 3.3).

A Power Exchange (PX) would provide a common trading platform. The PX should be designed for the purpose of dispensing short-term power available for trading through competitive bidding by inviting simultaneous anonymous bids from buyers as well as suppliers on day ahead hourly basis (Para 4.1.2 & 4.1.3)

Participation in the PX may be voluntary for the present (Para 4.2.3)

If the PX is put in place immediately, it may be hampered by lack of liquidity in supply due to meager surpluses, division of trade and lack of interest from suppliers (Para 7.2, 7.3 & 7.5)

Creation of Power Exchanges and wholesale markets in the mind of the policy makers and regulators was just sequential and not consequential. There are numerous examples in the discussion paper which indicate the market design for Exchanges was construed based on the immediate problems rather than taking a holistic long-term view for development of the markets. One might think that this wasn’t a terrible assumption to make at that time. The country was entrenched in chronic supply side shortages. Most of the trading was dependent on seasonal surpluses and captive generation.

But rather than turning to the well-known principle of Chesterton’s Fence12 and understanding the reasons behind the poor liquidity of tradable power and lack of interest from suppliers, the CERC discussion paper proposed setting-up Power Exchanges for utilizing the surpluses available from the captive and cogeneration plants and discoms.

Power Exchanges were established by early 2008 with a voluntary day ahead spot market as its first product. Day-ahead market is the bedrock of a good wholesale market. The Exchanges added to the aura of wholesale markets but the overall benefits to the market participants are yet to attain its true potential.

Firstly, transacting in the day ahead market was made physically and financially binding. Any change in physical position is therefore a cost in the form of deviation penalties. Since there was no real time market before 2019, managing physical positions had high costs for both discoms and generators13 when there is no right to revision in the day ahead market. Generator outages and abrupt swings in discom's demand are frequent feature of the Indian grid. This exposed both buyers and sellers to additional risks, specifically discoms who had to limit their exposure to day-ahead market because it could lead to backing down of low-cost power or DSM penalties.

Information asymmetries, coordination problems due to rigid operating procedures such as transmission capacity available for trades, application of transmission charges, separate scheduling, and dispatch processes for day ahead and long-term PPA market etc. have stumbled its efficiency and growth. Hence, despite functional wholesale markets, the benefits of self-scheduling long-term bilateral PPAs outweighed participation in wholesale markets and discoms largely continued to reduce reliance on the wholesale markets.

Pitfall #5: Electricity Derivatives – The Missing Markets

Since the prices in day-ahead market may vary considerably; market participants often wish to hedge against price risk. Specifically, because discoms have regulatory approvals in place for the price at which purchases can be made in the day-ahead market and generators have to invest in plants with a long lifetime which need steady cash flows for debt obligations. This called for introduction of a derivatives market in electricity. However, here, another thing got in the way. A jurisdictional disagreement between SEBI (formerly FMC) and CERC arose in 2010 about regulating the derivatives market. It denied both the buyers and sellers a mechanism to hedge prices, which in turn limited the growth of volumes in the day-ahead market.

Recently in 2020, the inordinately delayed SEBI-CERC jurisdiction issue was resolved, albeit through intervention by MoP. The cavalier approach shown by the judiciary, electricity and financial regulators in handling the matter have undermined the faith and halted the growth in wholesale markets.

Pitfall #6: Power Trading – An empty case for Power Traders

Even though the Electricity Act 2003 recognized power trading as a distinct activity, it probably remains the most misunderstood market.

In 2006, CERC imposed a flat trading margin cap of 0.04 Rs/kWh for transactions with a tenure of up to one year. The purported justification was restraining the high short-term bilateral prices and preventing power traders from profiting excessively due to the tight demand supply conditions. The margins for short-term trading have continued to be regulated ever since and are now capped at 0.07 Rs/kWh.

The fundamental problem here is the mistrust of profit14. The notion that traders would make super normal profits from short-term trading, but trade is not a zero-sum game. The truth is that trading is a positive-sum game. The market participants trade with each other because they are better off. Any intervention in this process reduces the value creation. A price cap might seem optically beneficial to the consumer in the short-term but it disincentivizes generators and traders which hurts the consumers in the long term due to restricted choice.

Over time, the short-term transactions in bilateral market have reduced. Volumes have moved to day-ahead market and overall market size has shrunk. Most of the trading is used for balancing the discom's seasonal surpluses and deficits. Such trade opportunities are invariably less than one year. The power traders act as agents to facilitate such transactions. They charge a commission in the process without taking market risks.

Volatility in electricity prices is highest in the short-term15. This is because both electricity demand and supply are highly inelasticity in the short-term. By capping the trading margins, regulatory framework has stifled innovation in power trading.

In general, trading margin should cover trader's O&M costs (such as employee expenses, office expenses, license and membership fees, business development expenses, legal expenses etc.), operating risks (such as credit, default, and late payment risks etc.), market risks (such as price risks and volume risks) and return on equity. Market risks taken by the traders might yield either profitable or loss-making outcomes. Therefore, a trader would attempt enough margin in good deals to make for the losses in bad deals. But, in the existing regulatory framework, the earnings are capped at 0.07 Rs/kWh, while there is no floor on the losses. Thus, there are no incentives for innovation and developing products that are better suited to market needs.

As a result, the trading market has not attracted any major players who could actively take positions in the market. What we have witnessed rather is smaller players who are happy with providing market access at very low costs. These players don't have any sophisticated risk management and risk capital allocation processes. They focus more on getting the buyers and sellers together and arrange for a back-to-back contract, thereby acting as brokers rather than traders. This also constrained the development of wholesale markets.

Pitfall #7: Financing Generation Expansion – Patronizing long term PPAs

Major financial institutions, particularly PFC and REC and their loan terms were also used to direct generation capacity addition along policy-favoured lines i.e., long-term coal-fired baseload PPAs. Non-recourse project financing through banks became the preferred route and therefore lenders prioritized financing projects which had secure offtake and revenue assurances backed by the sovereign guarantees. Long term PPAs were a key instrument for making such projects bankable.

Financial institutions’ capacity to develop lending arrangements for merchant sales through the wholesale market never got developed. Financial institutions were happy to fund perceived low risk projects that were backed by long-term PPAs. This not only crowded out the available funding but also increased the cost of capital for merchant generators.

So, summing up, the risks for participating in the wholesale markets were the following:

transmission availability – dispatch risks for both buyers and sellers; both settled for self-scheduling through long-term contracts sans these risks

increased cost of transacting in the wholesale market (transmission charges, deviation risks, operating charges) negated the very benefit that the wholesale markets provide i.e., low transaction cost as compared to long-term contracts

regulated coal markets - no assurance of coal supply to merchant plants increased the prices and limited the growth of wholesale markets whereas long-term PPAs helped secure coal supply

absence of a well-functioning post day ahead market (intra-day and real time market) reduced the volumes in the day-ahead market

lack of hedging instruments - no electricity derivative market to hedge exposure in wholesale markets - limited the growth of the market

tight capping of trading margins slowed the growth in the short-term bilateral market

debt market for financing merchant plants could not develop, thereby stalling the merchant capacities

CHAPTER THREE: THE CONSEQUENCES

Disproportionate emphasis on creating generation capacities, without consideration of wholesale markets eventually led to a playing field which is skewed towards long-term PPAs. The result before us is a highly inefficient market with a messy system of layering. The old Section 62 (state and central sector cost plus PPAs), Section 63 (reinvented private participation through case-1 and case-2) and a patchwork wholesale market coexist, and all have their own and unique regulatory framework for grid operations. In this system, the wholesale market is left at the mercy of any volumes which trickle down from the long-term PPA market.

It is clear that there was no real growth in wholesale markets. Whatever growth has been is a spillover effect of the long-term PPA market. Most of the trades in wholesale markets are from discoms who are optimizing their daily surpluses or deficits. The design favored long-term PPAs increasing the costs for wholesale markets. Rather, we can go a step further and say that the success of the long-term PPA market has come at the cost of the wholesale market. Thus, the policy and regulatory apparatus underlying the Electricity Act 2003 has not produced a genuine “two-tier market solution” in which both the long-term PPA market and a wholesale market could operate seamlessly and flourish.

What has emerged instead, is a patchwork “two-tier market solution” in which the wholesale market is merely grafted onto a long-term PPA market. The policy and regulatory apparatus came as a package for long-term PPAs but only as a patchwork for wholesale markets. Thus, the wholesale markets have existed in form for the last 15 years but not in function. In other words, when the market was designed, the wholesale markets were never considered as an objective. It was only an afterthought, much like gift-wrapping the "two-tier market solution" with wholesale markets, with the latter being reduced to the status of a wrapper. This is why Paul Joskow16, one of the early pioneers of electricity sector deregulation, in his paper “The Difficult Transition to Competitive Electricity Markets in the U.S” says the following:

“One of the most challenging things to explain to people who are not familiar with the unusual attributes of electricity is that wholesale electricity markets do not design themselves but must be designed as an integral central component of a successful electricity restructuring and competition program”

CHAPTER FOUR: THE INCENTIVES

Despite restructuring and deregulation induced by the Electricity Act 2003, the government still retains most of the control over legislation, policies, regulations, procurement (government owned discoms), and even lending (PFC/REC and PSU banks). Thus, the kind of institutional structure that has evolved has left many avenues or entry points for the private sector to influence these government institutions. Due to this, a constituency has emerged within the private sector that has incentives in perpetuating the long-term PPA markets. The constituency fosters a symbiotic relationship between the government and businesses which has promoted a form of rent-seeking capitalism. For instance, consider the following:

Case-1 and Case-2 policy favored a particular technology, in this case, coal-fired generation. Developers didn’t have to price-in any technology, transmission, fuel, off-take, credit, and regulatory risk. PPAs offered a fixed rate of return over a period of 25 years. Land, coal supply, change in law, tax benefits etc. were all extended to the developers

Banks also preferred not to take any market risk by favoring long-term PPAs, therefore had less incentives to monitor whether the risks (technology, regulatory, price, environment etc.) were priced-in correctly or not. Banks got used to funding projects backed by long-term PPAs building a strong concentration of lending and disbursement to long-term PPA projects leaving smaller room for innovation and wholesale market-based projects

Over time, the supporters of long-term PPA markets have become powerful proponents of this policy. It is now almost impossible to make a contrarian voice heard in the power corridors of various government institutions. The private sector has accomplished this by establishing a subservient relationship with the government institutions. The biggest strength of private sector is the sycophancy of these institutions in anticipation of commercial advantage and favourable decisions.

The private sector has figured out subtle ways of intermediation with these institutions. They work directly with the MoP and state governments in case of specific individual issues and indirectly through lobbies for collective action problems. All major industry bodies, including CII, FICCI, Assocham etc. have committees representing power sector. More operational and granular issues are taken up through other power sector specific lobbies like APP, WIPPA etc. These associations create highly institutionalized and responsive interactions between the policy making bodies like MoP, MoC, and CEA/CERC etc. and the businesses. The government being a direct beneficiary of public sector companies works to take care of the interests of its own public sector entities.

The rent seeking mentality of the constituents therefore blocks any entrepreneurial capitalism and development of wholesale markets. This is the underlying reason for perpetuation of “pro-business policies17” and silencing of the “pro-market policies” or in other words the apathy of policy and regulatory apparatus towards the wholesale markets.

Another problem here could also be the lack of “tacit knowledge” about how to create a competitive wholesale market. Most of the private sector businesses either lack deep knowledge or are reticent about how the policy and regulatory apparatus should be crafted for a wholesale market. Not a single association, or a large private company has ever presented a long-term vision for wholesale markets in the country. It doesn’t matter what happens to the wholesale markets, as long as the private sector has a steady flow of deals with benevolent policies and regulations in the form of long-term PPAs.

In this sense, there is also selfishness within the private sector, which is not thinking about the efficiency of wholesale markets. They are often looking for short-term deals rather than trying to create value through wholesale markets. A defensive approach to deal with problems as they arise is preferred over a proactive approach to shape wholesale markets. They are more concerned about their quarter-to-quarter earnings and high valuations because of deal pipeline. A dysfunctional wholesale market is therefore better for private players that excel in relationship management with governments. Such a compact for intermediation between the institutions and businesses has been a continuing problem of the sector. The outcome is that the big business houses are benefited in the name of deepening power markets.

Even with the best intentions of some policymakers or some private players, no genuine progress could be made in the sector that is deeply entrenched in patchwork due to the vulnerabilities that have been exploited over the decades. Hence, the market design continues to be a jury-rigged result, a collection of incremental patchworks – highly innovative at few places, mundane at most and Rube Goldberg in yet others18.

CHAPTER FIVE: THE DYSFUNCTIONS

The “two-tier market solution” had sought to repair the dismal condition of the sector. Instead, the model has generated distinctive forms of dysfunctions in both the long-term PPA and the wholesale markets.

Firstly, the design has propagated an uneven sharing of risks and returns in long term PPA market. This goes against every contractual standard that has been established globally. The promoters have retained all the upsides during good times and very little downside in bad times by resorting to litigation.

The capital flight into the long-term PPAs has pushed the profit margins down. Aggressive bidding has mired companies in retrospective renegotiations. Instances of litigations have grown exponentially. There isn't a single private generator that hasn't engaged into multiple litigations to improve profitability.

The conspicuous examples are the failure of UMPPs - CGPL Tata and Mundra Adani. UMPPs were awarded on the lowest tariffs but managed to have their tariffs increased through litigation. Several committees were formed by both the union power ministry and state governments to ensure the projects do not end up in bankruptcy. The governments have come to their rescue even if bankruptcy was forced by developers’ themselves through wrong assumptions19. Similarly, no action was taken against the developer of two UMPPs, Krishnapatnum and Tillaya, which were awarded through competitive bidding, where the developer walked away from the project. Shelving of Krishnapatnum also led to sustained transmission congestion until 2015 in the Southern Region resulting in huge financial losses to the discoms20. This shows that there is always room for executive discretion in the long-term PPA market.

But more importantly, what this also shows is that the holders of long-term PPAs have enjoyed “riskless capitalism”. They profited in good times and were bailed out in bad times by the banks. Riskless capitalism21 is a term first used by Ex-Governor of Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Dr. Raghuram Rajan during one of his talks in November 2014.

Rajan, too, believes that for sustained growth, India must shift away from a big business-oriented policy framework towards a much more broader pro-market one. An excerpt from his talk is reproduced below:

“Risk taking inevitably means the possibility of default. An economy where there is no default is an economy where promoters and banks are taking too little risk. What I am warning against is the uneven sharing of risk and returns in enterprise, against all contractual norms established the world over – where promoters have a class of “super” equity which retains all the upside in good times and very little of the downside in bad times, while creditors, typically public sector banks, hold “junior” debt and get none of the fat returns in good times while absorbing much of the losses in bad times.”

“The consequences of the delays in obtaining judgements because of repeated protracted appeals implies that when recovery actually takes place, the enterprise has usually been stripped clean of value. The present value of what the bank can hope to recover is a pittance. This skews bargaining power towards the borrower who can command the finest legal brains to work for him in repeated appeals, or the borrower who has the influence to obtain stays from local courts – typically the large borrower. Faced with this asymmetry of power, banks are tempted to cave in and take the unfair deal the borrower offers. The bank’s debt becomes junior debt and the promoter’s equity becomes super equity. The promoter enjoys riskless capitalism – even in these times of very slow growth, how many large promoters have lost their homes or have had to curb their lifestyles despite offering personal guarantees to lenders?”

Arvind Subramanian, Ex Chief Economic Adviser summed the state of policy and regulatory affairs in India appropriately by simply articulating the long-standing policy and regulatory concerns to deal with failed businesses as a journey akin to “Socialism with restricted entry to Capitalism without exit"

While the private generators have treated discoms as a means of rent extraction through their long-term PPAs. The cash-strapped discoms have reciprocated by making it extremely difficult to collect promised revenues.

The discoms are straddled with a high fixed costs burden. The two-part tariff structure of PPAs has required discoms pay the fixed costs even when not consuming a single unit of electricity. This has led to sharp escalation of the costs for discoms. Wholesale prices, in some years, were driven down by surplus discoms to levels where purely market-based investment was no longer profitable. While supply disruptions caused by litigation and nonresolution of legal disputes sent the prices soaring in the wholesale markets in some years. The resulting volatility in wholesale markets has also damaged its credibility.

As of now, nearly 40GW coal and 28GW of gas plants are stressed and another 23GW coal plants that were in various stages of implementation have been shelved. Lack of long-term PPAs and fuel availability are cited as the main cause for this stranded capacity. Banks and financial institutions have written off large amounts of capital. A giant fire sale for the distressed assets is ongoing where a select group of bidders like Adani, JSW and TATA power have prospered by gaining scale at low costs. A small fraction of debts are being recovered by banks. Ownership patterns are changing. The sector may be headed towards Russian style oligarchy22. In many respects, such destruction is ironic.

On the other hand, the accumulated losses of discoms are piling. Last, it was reported as over 3 lakh crore. Although, high cost of long-term PPAs is not the only reason for this plight of discoms but power procurement through long-term PPAs is 75-80% of the discom’s average cost of supply. If the overall objective is to bring down costs, the emphasis must be on fixing the process of bulk power procurement and fair competition in the long-term PPAs. We recommend that fixing the distortions in the wholesale market must be treated as an immediate priority over retail competition and privatization.

Overall, these state-of-affairs have left the wholesale markets in a “low-level equilibrium trap23”. Problems of transmission access, limited liquid buy and sell volumes, volatility, and gross underutilization due over contracting of coal fired PPAs, and financing regulations have kept the generators and discoms out of the wholesale markets.

Up to this point in our essay, we have concentrated on the impact of structural and institutional reforms up to 2014. The reforms resulted in a market equilibrium that was stable. But not optimal. Stable because it has eliminated capacity shortages and none of the participants want to come out of it. Suboptimal because the cost of transactions in both long-term PPA and wholesale markets increased.

CHAPTER SIX: THE DÉJÀ VU

In 2014, UPA made exit for NDA. Every regime has a narrative. If UPA was about structural reforms for coal fired long-term PPAs. NDA is about long-term PPAs for renewables.

Modi’s first step in the sector was a pie in the sky, declaring to the world 175 GW of solar and wind by 2022. The narrative demanded creative thinking and radical choices. However, once again, the past played in the present. Pro-business policies were chosen as the “route-to-market” for renewables.

Therefore, the only visible difference in our “two-tier market solution” after 2014 is that the long-term coal-fired baseload physical delivery based PPAs have been replaced with long-term fixed price physical delivery based “must run” renewable energy PPAs. Most of the PPAs are in solar with some sprinkling of wind.

No doubt, the goal of adding renewables is both noble and critical. But what about the modus operandi for scaling renewables?

It is the same old “maggi magic masala” recipe:

Create demand for renewables by increasing the RPO levels, mitigate technology, tariff, and financing risks etc. through long-term PPAs

Create another monopoly like CIL, now SECI – a highly credit worthy entity for providing bankable PPAs

Throw in some more incentives – land parcels, UMPP scale parks, transmission connectivity, waiver for transmission charges etc.

Our 2-minute maggi noodles are ready. Critical issues such as grid security were left to system operators to figure out. Since the jury is still out whether the renewables can function without banking and wheeling policy.

The policy framework for scaling renewables has yielded fantastic results. We are beating our drums at the annual COPs. Since 2014, ~70GW of renewables have been added till date. Another 40-50GW is in pipeline with more central and state auctions being announced every quarter. Now, we are adding more renewables annually than coal. Although there is some offtake resistance by buyers now, the runway is extended by bringing exotic contract structures – RTC bids, Profile bids, Hybrid bids and so on. The nexus will try to engineer synthetic and frugal solutions through long-term PPAs, but not allow the market forces to optimize the supply requirements naturally.

All of us have heard about Einstein’s definition of Insanity24

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”

The renewable story in India is just the mirror image. As was the case with coal, long-term fixed price contracts between generators and discoms continue to be the dominant transaction mechanism for renewables. Renewables are also anchored in long-term PPA markets. Therefore, the same risks that plagued the conventional assets for adopting wholesale markets have petrified renewable developers to a far greater extent because renewables are much more vulnerable due to inherent intermittency and variability

LTA transmission charges for merchant renewables are massive due inherent low PLFs. Initially, the transmission charges were waived for long-term PPAs only. Later on the waivers were extended to merchant capacities. Consumers therefore opted for long-term PPA over wholesale markets

Rescheduling rigidities in wholesale markets expose renewables to higher deviation penalties. For renewables, there is a strong inverse correlation between forecast accuracy and lead time to delivery. Accordingly, long-term PPAs have a “free option25” to change schedules four-time blocks ahead of delivery. However, the legacy structures of wholesale markets continue to haunt renewables too and merchant renewables suffer because they are required to commit sacrosanct schedules for day-ahead and short-term bilateral contracts hours and days in advance

Hedging mechanisms such as electricity derivative markets are still missing

Naturally, the same policies and regulations that had dampened the wholesale market for conventional energy cannot be expected to deepen the wholesale market for renewables26.

The growth in renewables has already arrived through long-term PPAs. We are readying ourselves for new targets - 500GW by 2030. Yet, we have not solved the questions related to transmission connectivity, access and charges, deviation settlement rules, financial markets and so on for wholesale markets. This contrasts with Europe and the United States where these questions had been largely solved before renewables growth began.

It is unfortunate that we haven’t learned our lesson. Policymakers have retreated to the “pro-business policy” model that was previously used for coal fired capacity expansion. It is hardly surprising that renewables are also mired in ‘change in law’, 'tariff disputes', 'basic custom duty changes' etc. The wholesale market for renewables continues to be a chimera.

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE COLLATERAL DAMAGE

The real impact of indifference towards wholesale markets calls to mind the “Layering Model” of Adam Tooze – one of the most respected economists of recent times.

Tooze defines layering as

“a dynamic whereby the concerns of interest groups related to each distinct crisis overlap ‘to create layered social problems: current problems with historical problems, tangible interest problems with ideological problems, political problems with non-political problems; all intersecting and interfering with one another”

Simply put, the "two-tier market solution" has experienced “policy, regulatory and institutional layering”. Layering occurred because of new policy, regulatory, and institutional dynamics being grafted as patchwork onto pre-existing structures rather than developing them to meet the needs of markets.

Existing structures are often difficult to dismantle because they create constituencies in both the public and private sectors that want to protect them. Therefore, it is argued that gradualist layered approach to reforms rather than simply replacing the status quo is a strategic move by policymakers to prevent any resistance against the new structures.

This is the reason why most structural reforms never completely erase the older structures. But layering as alternative and as carried out in the power sector has resulted in a messy system of segmentation. The wholesale market has emerged entangled with a preexisting structure of long-term PPAs both coal-fired baseload PPAs and now renewables based ‘must run’ PPAs. The sum of inefficiencies of the two markets taken together i.e., long-term PPA markets and wholesale markets ‘as a whole’ is greater than the sum of its constituent parts.

It is important to note that while many consider gradualism as a quiet revolution producing cumulatively significant changes over time. But segmentation which is inherent in any gradualist approach isolates the unreformed parts from reformed parts. The incremental layering leaves multiple entry points for rent-seekers in both private and public sectors to influence policy for protecting their own turfs. Some recent examples worth highlighting here would be the following policies by MoP:

Scheme for flexibility in generation and scheduling of thermal/hydro power stations through bundling with renewable energy and storage power27

Concept Note on pooling of tariff of 25 year plus thermal/gas generating stations

Both of these policies will create winners and losers. Winners here would be public sector enterprises and losers will be the discoms and ultimately consumers. Therefore, no brainer why these policies also can’t be categorized as pro-business policies.

The ‘two-tier market solution’ in its current form lowers both the short-run28 (static) efficiency and long-run29 (dynamic) efficiency, maybe significantly. In the short run, many low-cost generators don’t get dispatched due to scheduling, coordination, information asymmetry and other problems arising from the regulatory design for grid operations. In the long-run, the incentives for development of optimal capacity/contract mix go for a toss since the short-run efficiency is lost30. In this way, the long-term PPA market and wholesale market exist in an economically inefficient operation, ensuring that the overall system remains insolvent.

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE TRANSFORMATION

The “two-tier market solution” hasn’t delivered what it was supposed to. However, it is easy to see faults. But harder to figure out solutions. If this is the case, what can be done?

There is an old saying in the field of drinking water

“Don’t fix the pipes; fix the institutions that fix the pipes”.

We don’t want to take a cynical view on the long-term PPAs. PPAs are a good way for discoms to lock in lower prices over longer periods. But it is not advisable for policy to unduly favour and decide on the duration, amount and technology of contracts required by the discoms.

The seen benefit of PPAs is lowering the costs of capital, but the unseen drawback is the cost of making imperfect choices in the long run. The costs are not borne by the investors but are socialized on the consumers. The real examples for this are not only the seen fixed charges of long-term coal fired PPAs but also the unseen environmental costs that these PPAs are carrying today.

Our newsletter doesn’t subscribe to market fundamentalism. According to free market orthodoxy, market dynamics will correct failures in due course. But we think that failures may come at high costs and undermine market credibility. Therefore, free market orthodoxy is not the answer we propose.

The goal of this essay is to draw attention to the difficulties of creating a “two-tier market solution”. Understanding the distinction between rent-seeking and entrepreneurial markets and crafting policies and regulations that are pro-market rather than pro-business are essential.

Thus far, we have been using the binary “long term PPA markets” versus “wholesale markets”. However, the reality is much more nuanced. It doesn’t come in these neat binaries. Grey is the only shade in long term PPA versus wholesale markets. The best of the wholesale markets may come with negative consequences, while the long term PPAs may also have some positive fallouts. Therefore, in a "two-tier market solution", the long-term PPA and wholesale markets are the two poles around which the markets need to be coalesced. Both have intrinsic value if there is minimal policy and regulatory arbitrage.

The peculiarities of electricity necessitate a variety of contracts, particularly in different maturities31. Generators and discoms should be able to trade on different marketplaces. Under ideal conditions, arbitrage and competition ensure that prices in the two markets are equalised.

The balance between the long-term PPAs and wholesale markets should therefore be a function of the market forces rather than deliberate policy tools and regulatory intervention.

Therefore, the key question to ask is not “what the size of a long-term PPA market should be vis-à-vis a wholesale market”? That is a false narrative. But the debate should be around crafting policy and regulatory apparatus which creates enough checks and balances to allow the two markets to operate, optimize and size dynamically.

Deepening of wholesale markets has been a long-standing policy goal. However, this has not been realized in over two decades. To make this happen, wholesale markets require pro-market policy orientation. Regulatory gaps must be plugged such as distortions in DSM, transmission connectivity, access and charges, restrictions on purchasing electricity from the wholesale market, fuel allocation policy and pricing, hedging mechanisms including financial derivatives etc. This will be only fair. These systemic constraints limit the intrinsic value of wholesale markets and the “two-tier market solution” as a whole. Policy and regulations should be transformative rather than facilitative in this regard.

CHAPTER NINE: THE SECOND RUNWAY

Evidently, we have missed the runway offered by the Electricity Act 2003 for deepening of markets. Fortunately, the energy transition has offered us another runway.

The noble and lofty objectives of deep decarbonization of our power sector have put electricity markets back in focus. Global experience indicates that market reforms and commensurate changes to grid operating procedures to integrate renewables can alleviate investments in physical infrastructure. We are seeing various interventions from policymakers at different points of the spectrum, some of them appear to be extensions of the continuing patchwork and some genuine attempts to reform the sector.

In this regard, we would like to reiterate that we do not see reliance on long term PPA markets as a deterrent to deepening of markets. But we identify inordinate focus on physical delivery of contracted long-term PPAs as the culprit. Accordingly, the solution too lies in finding a mechanism for simultaneous, symbiotic, and efficient co-existence of long-term PPA markets and deep wholesale markets. The same may be achieved by decoupling contracting and dispatch. Understanding this fundamental principle is key to unlocking the true potential of the “two-tier market solution”.

As indicated previously, participants require contracts of differing maturities for efficient system operations. These may range from years ahead to delivery in the next hour. Each of these contracts may be traded through separate market places because of their own nuances. However, physical delivery of each of these contracts results in out-of-merit dispatch and therefore loss of static and dynamic efficiency as is witnessed in the Indian context.

The concept of decoupling contracting, and dispatch suggests that bilateral long-term contracting for assets may continue for capacity creation, resource adequacy and hedging needs. However, they must exist only in the financial form and real-time dispatch of electricity is through wholesale markets. In a decoupled regime, participants would trade positions and not electricity across markets of different maturities. And the ultimate trade prior to gate-closure determines physical delivery obligations of electricity.

Now, there might be apprehensions about how electricity traded across different market places may be dispatched in a single market. There are nuances about the nature of origin, tariff, commercial aspects, etc. Dear readers may note that the physical attributes of electricity make it a classic commodity which is completely homogenous and indistinguishable, and its flows are subject to laws of physics only. The fun fact being current flows from positive to negative and everything else is accounting. None of the attributes require preservation. The only ranking factor in such a unified physical dispatch market is the variable charge. Accounting takes care of all other linked financial transactions.

This mechanism has the benefit of improving both static and dynamic efficiency. Exchange of electricity through wholesale markets will ensure efficient dispatch besides rendering depth to the markets and improve signaling of new capacity requirements. Contracting through bilateral routes will continue to ensure that primary markets for capacity creation remain functional.

Since contracts in such regime would be financial positions only, low transaction costs will enable seamless re-trading of positions thus enable resource sharing, better absorption of renewables and leverage diversity factors across the geographical footprint. There are very few immutable, universal rules that apply across all developed electricity markets. This is one of them.

The idea of decoupling contracts and dispatch is not novel in India. It has already been making rounds for a few years now. It was first proposed by CERC in its Discussion Paper on Market Based Economic Dispatch of Electricity: Re-designing of Day-ahead Market (DAM) in India32. This was followed by another Concept Note by Ministry of Power33. We, however, feel that though the end-state is desirable, achieving the same through coercion may not be the best possible mechanism34.

An alternative mechanism, where discoms “voluntarily” bid their entire day ahead demand and offer their entire supply portfolio on Exchanges appears to be a simpler at this stage. With implementation of GNA, most of the distortions related to transmission access and pricing have been sorted. Discoms will route their dispatch through Exchanges if the benefits are more than the transaction fee of 0.02 Rs/kWh. Further, Exchanges might also automatically bring down their transaction fee by striking deals with discoms for attracting more volumes. Higher volumes in day-ahead market would also increase the liquidity of the real-time markets as discoms would balance their day ahead position in real-time market.

This solution appears to be within the self interest of discoms, less painful and more endurable than a sudden transition to MBED which could face serious setbacks due to the inherent inertia that has piled up due to the myriad of patchwork done so far. With coal making way for other environmentally benign technologies, there may be merit in attempting to reset the complex architecture which has coal fired long-term PPAs as its genesis.

Change from the status quo is going to be painful and the Lindy Effect35 is on full display. However, we need to be cognizant of the limitations of the current patchwork and channelize efforts to reorient extant practices and procedures rather than building more patchwork. The solution lies in identifying real barriers that have prevented market participants from leveraging spot markets and bringing down those barriers. Cosmetic changes will only create a mirage of progress – which would be more of activities and not achievements.

CHAPTER TEN: THE CONCLUSION

The Electricity Act 2003 started a hope for embracing markets. However, the underlying policy and regulatory apparatus has not delivered on that hope. The great tragedy of the “two-tier market solution” is the illusion of the wholesale markets, where the markets exist only in form and not in function.

The dream of efficient wholesale markets is beyond attainment if we continue the current course. The course where the policy and regulatory apparatus and institutions have attempted to try hyper multi-objective optimization. The sector has performed sub optimally, ultimately creating a system that meets none of the objectives.

Will our policymakers and regulatory bodies have the tenacity to reconsider their approach and design a solution where pro-market policies take precedence over pro-business policies? There are no easy answers. However, if nothing changes, the path to deeper wholesale markets may become more difficult, time consuming or forever remain a “Jumla”.

EPILOGUE

“Electricity is an extraordinary commodity – not one to be used in economics textbooks to demonstrate the purported laws of supply and demand”.

For a considerable period of the twentieth century, electricity has been the textbook example of why markets for certain commodities do (should) not exist and has dominated the mainstream discourse surrounding natural monopolies. Samuelson opined competition in electricity to be “obviously uneconomical” while Mconnell held that

“In a few industries economies of scale are particularly pronounced, and at the same time competition is impractical, inconvenient, or simply unworkable. Such industries are called natural monopolies, and most of the so-called public utilities - the electric and gas companies, bus and railway firms, and water and communication facilities - can be so classified. . . It would be exceedingly wasteful for a community to have a number of firms supplying water or electricity. Technology is such in these industries that heavy fixed costs of generators, pumping and purification equipment, water mains, and transmission lines are required....” (McConnell 1960)

Joskow and Schamlensee in their seminal work “Markets for Power: An Analysis of Electrical Utility Deregulation, 1983” first tinkered around the idea of allowing free market forces to replace government regulation in the electric power industry. The rest as we know is history. By the late 1990s36, several states in the United States started to restructure the electricity sector, replacing regulated and vertically integrated utilities by wholesale and retail markets open to many competitors.

In 1991, Ministry of Power was known as the Power Ministry

Imbalance mechanism in India is known as DSM (Deviation Settlement Mechanism)

DEEP (Discovery of Efficient Electricity Price) is a e-Bidding and e-Reverse auction portal for procurement of short-term power by DISCOMs. The web portal seeks to ensure seamless flow of power from seller to buyer. The portal is an initiative of the Ministry of Power with the objective to introduce uniformity and transparency in power procurement by the DISCOMs and at the same time promote competition in electricity sector.

Source of data for graph is the Annual Reports of the CERC Market Monitoring Cell

https://www.amazon.in/Marketcraft-Governments-Make-Markets-Work/dp/019069985X

A deep connection in transmission system planning parlance means that the connectivity for a generator is granted by considering grid reinforcements at the interconnection point as well as the deeper mesh for seamless flow of power. In India, the grid reinforcement at the interconnection point is known as Associated Transmission System (ATS) and in the deeper mesh is known as the System Strengthening. The customers availing LTA get firm access to the transmission network and therefore must pay the transmission charges for both the ATS and system strengthening.

A shallow connection in transmission system planning parlance means that connectivity for the generator is granted by considering only the reinforcements required at the interconnection point. The transmission access is therefore non-firm and dispatch will be allowed only in case there is enough capacity in the system to absorb the power.

(1) December 2013: Concept of GNA by CEA; (2) September 2014: CERC Staff Paper on Transmission Planning, Connectivity, Long Term Access, Medium Term Open Access and other related issues; (3) August 2015: Committee on Relinquishment of LTA; (4) February 2016: Report of Task Force (formed by CERC) on Planning Regulations; (5) July 2016: Report of Committee on Assessment/Determination of Stranded Transmission Capacity and Relinquishment charges; (6) September 2016: Mata Prasad Committee (formed by CERC) Report for Review of Transmission Planning, Connectivity, Long Term Access, Medium Term Open Access and other related issues proposed GNA; (7) April 2017: Draft Regulations on Planning by CERC considering Task Force and Mata Prasad Committee Report and proposed to delete Part-III of IEGC; (8) July 2017: Task Force for Review of Framework for Point of Connection Charges (PoC); (9) November 2017: Draft Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (Grant of Connectivity and General Network Access to the inter-State transmission system and other related matters) Regulations, 2017; (10) March 2019: Bakshi Committee Report on Review of Framework for Point of Connection Charges; (11) August 2020: MoP formulated draft Transmission System Planning and Recovery of inter-State Transmission Charges Rules, 2020

The “missing money problem” refers to the idea that prices for energy in competitive wholesale electricity markets may not adequately reflect the value of investment in the resources needed for reliable electric service.

https://cercind.gov.in/13042007/signature.pdf

Chesterton’s Fence: The principle that reforms should not be made until the reasoning behind the existing state of affairs is understood

With introduction of Real Time Market (RTM), the discoms are now naturally able to manage their day ahead positions in real time but generators lack this flexibility and can manage their position in real time only during forced outages.

For mistrust of Profit, read the primer section of essay “Price Ceilings on Power Exchanges: Profit is not a dirty word”, Jai & Veeru;

In India, the short-term volatility is on account of weather uncertainties (heat/cold waves, weak/normal/active monsoon, early/late arrival/exit of monsoon), coal supply disruptions during monsoons, disputes over PPAs, state/central election etc.

http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/45001

The distinction between the ‘pro-business’ and ‘pro-market’ policies in the Indian context was made by Dani Rodrick and Arvind Subramaniam in 2004 in their seminal paper “From “Hindu Growth” to Productivity Surge: The mystery of Indian Growth Transition”. A pro-business policy favours the incumbents. For instance, incentives for increasing production, concessional land allocations, allowing capacity expansion for existing players, and tax rebates to help existing businesses scale up their operations. A pro-market policy on the other hand refers to removing impediments to all economic activity. For instance, the substantial dismantling of the “license-permit-quota” raj through economic liberalization in 1991 was a pro-market reform as it reduced entry barriers for new, old and yet-to-be-born firms in the market alike. Such reforms are pro-competition as they level the playing field for new entrants against established players, who have blessings of the government. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/biblio/12571588

Adopted from The Grid, Gretchn Bakke. A Rube Goldberg machine, named after American cartoonist Rube Goldberg, is a chain reaction–type machine or contraption intentionally designed to perform a simple task in an indirect and (impractically) overly complicated way. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rube_Goldberg_machine

https://scroll.in/article/915109/adani-power-project-was-on-the-brink-of-bankruptcy-but-the-bjp-government-in-gujarat-saved-it

The transmission system planned for Krishnapatnum UMPP was build with the intention of exporting some power from Southern Region (SR) to the New Grid as the UMPP had shares in Western Region (WR) also. With shelving of UMPP, the transmission evacuation from Southern Region also needed to be revisited which delayed the interconnections between WR and SR. It was only through regulatory approval by CERC that finally the 765 kV double circuit transmission line got built between the two regions and the congestion eased out.

https://rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_SpeechesView.aspx?Id=929

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_oligarchs#:~:text=Russian%20oligarchs%20(Russian%3A%20%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%B3%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%85%D0%B8%2C,dissolution%20of%20the%20Soviet%20Union.

Nelson’s theory of low-level equilibrium trap: The low-level equilibrium trap is a concept in economics developed by Richard R. Nelson, in which at low levels of per capita income people are too poor to save and invest much, and this low level of investment results in low rate of growth in national income.

https://www.businessinsider.in/thelife/culture/12-famous-quotes-that-always-get-misattributed/articleshow/23671857.cms

The option to revise schedule in a long-term PPA has zero costs

Deeper questions on the Idea of Green Day Ahead Markets (GDAM) by Jai & Veeru.

https://powermin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Scheme_for_Flexibility_in_Generation_and_Scheduling_of_Thermal_Hydro_Power_Stations.pdf

Short-run or static efficiency is the least cost operation of existing resources (generators or contracts)

Long-run or dynamic efficiency is the right quantity and mix of resources (generators or contracts)

Short-run efficiency is a necessary condition for long-run efficiency

Maturity is the lead time between contracting and delivery

The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Market Based Economic Dispatch (MBED),

The Lindy effect (also known as Lindy's Law) is a theorized phenomenon by which the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things, like a technology or an idea, is proportional to their current age

Chile was the pioneer in Power Sector deregulation in the early 1980s